4 May 2016

Using Roslyn code fixes to make the "Friction-less immutable objects in Bridge" even easier

This is going to be a short post about a Roslyn (or "The .NET Compiler Platform", if you're from Microsoft) analyser and code fix that I've added to a library. I'm not going to try to take you through the steps required to create an analyser nor how the Roslyn object model describes the code that you've written in the IDE* but I want to talk about the analyser itself because it's going to be very useful if you're one of the few people using my ProductiveRage.Immutable library. Also, I feel like the inclusion of analysers with libraries is something that's going to become increasingly common (and I want to be able to have something to refer back to if I get the chance to say "told you!" in the future).

* (This is largely because I'm still struggling with it a bit myself; my current process is to start with Use Roslyn to Write a Live Code Analyzer for Your API and the "Analyzer with Code Fix (NuGet + VSIX)" Visual Studio template. I then tinker around a bit and try running what I've got so far, so that I can use the "Syntax Visualizer" in the Visual Studio instance that is being debugged. Then I tend to do a lot of Google searches when I feel like I'm getting close to something useful.. how do I tell if a FieldDeclarationSyntax is for a readonly field or not? Oh, good, someone else has already written some code doing something like what I want to do - I look at the "Modifiers" property on the FieldDeclarationSyntax instance).

As new .net libraries get written, some of them will have guidelines and rules that can't easily be described through the type system. In the past, the only option for such rules would be to try to ensure that the documentation (whether this be the project README and / or more in-depth online docs and / or the xml summary comment documentation for the types, methods, properties and fields that intellisense can bring to your attention in the IDE). The support that Visual Studio 2015 introduced for customs analysers* allows these rules to be communicated in a different manner.

* (I'm being English and stubborn, hence my use of "analysers" rather than "analyzers")

In short, they allow these library-specific guidelines and rules to be highlighted in the Visual Studio Error List, just like any error or warning raised by Visual Studio itself (even refusing to allow the project to be built, if an error-level message is recorded).

An excellent example that I've seen recently was encountered when I was writing some of my own analyser code. To do this, you can start with the "Analyzer with Code Fix (NuGet + VSIX)" template, which pulls in a range of NuGet packages and includes some template code of its own. You then need to write a class that is derived from DiagnosticAnalyzer. Your class will declare one of more DiagnosticDescriptor instances - each will be a particular rule that is checked. You then override an "Initialize" method, which allows your code to register for syntax changes and to raise any rules that have been broken. You must also override a "SupportedDiagnostics" property and return the set of DiagnosticDescriptor instances (ie. rules) that your analyser will cover. If the code that the "Initialize" method hooks up tries to raise a rule that "SupportedDiagnostics" did not declare, the rule will be ignored by the analysis engine. This would be a kind of (silent) runtime failure and it's something that is documented - but it's still a very easy mistake to make; you might create a new DiagnosticDescriptor instance and raise it from your "Initialize" method but forget to add it to the "SupportedDiagnostics" set.. whoops. In the past, you may not realise until runtime that you'd made a mistake and, as a silent failure, you might end up getting very frustrated and be stuck wondering what had gone wrong. But, mercifully (and I say this as I made this very mistake), there is an analyser in the "Microsoft.CodeAnalysis.CSharp" NuGet package that brings this error immediately to your attention with the message:

RS1005 ReportDiagnostic invoked with an unsupported DiagnosticDescriptor

The entry in the Error List links straight to the code that called "context.ReportDiagnostic" with the unexpected rule. This is fantastic - instead of suffering a runtime failure, you are informed at compile time precisely what the problem is. Compile time is always better than run time (for many reasons - it's more immediate, so you don't have to wait until runtime, and it's more thorough; a runtime failure may only happen if a particular code path is followed, but static analysis such as this is like having every possible code path tested).

The analysers already in ProductiveRage.Immutable

The ProductiveRage uber-fans (who, surely exist.. yes? ..no? :D) may be thinking "doesn't the ProductiveRage.Immutable library already have some analysers built into it?"

And they would be correct, for some time now it has included a few analysers that try to prevent some simple mistakes. As a quick reminder, the premise of the library is that it will make creating immutable types in Bridge.NET easier.

Instead of writing something like this:

public sealed class EmployeeDetails

{

public EmployeeDetails(PersonId id, NameDetails name)

{

if (id == null)

throw new ArgumentNullException("id");

if (name == null)

throw new ArgumentNullException("name");

Id = id;

Name = name;

}

/// <summary>

/// This will never be null

/// </summary>

public PersonId Id { get; }

/// <summary>

/// This will never be null

/// </summary>

public NameDetails Name { get; }

public EmployeeDetails WithId(PersonId id)

{

return Id.Equals(id) ? this : return new EmployeeDetails(id, Name);

}

public EmployeeDetails WithName(NameDetails name)

{

return Name.Equals(name) ? this : return new EmployeeDetails(Id, name);

}

}

.. you can express it just as:

public sealed class EmployeeDetails : IAmImmutable

{

public EmployeeDetails(PersonId id, NameDetails name)

{

this.CtorSet(_ => _.Id, id);

this.CtorSet(_ => _.Name, name);

}

public PersonId Id { get; }

public NameDetails Name { get; }

}

The if-null-then-throw validation is encapsulated in the CtorSet call (since the library takes the view that no value should ever be null - it introduces an Optional struct so that you can identify properties that may be without a value). And it saves you from having to write "With" methods for the updates as IAmImmutable implementations may use the "With" extension method whenever you want to create a new instance with an altered property - eg.

var updatedEmployee = employee.With(_ => _.Name, newName);

The library can only work if certain conditions are met. For example, every property must have a getter and a setter - otherwise, the "CtorSet" extension method won't know how to actually set the value "under the hood" when populating the initial instance (nor would the "With" method know how to set the value on the new instance that it would create).

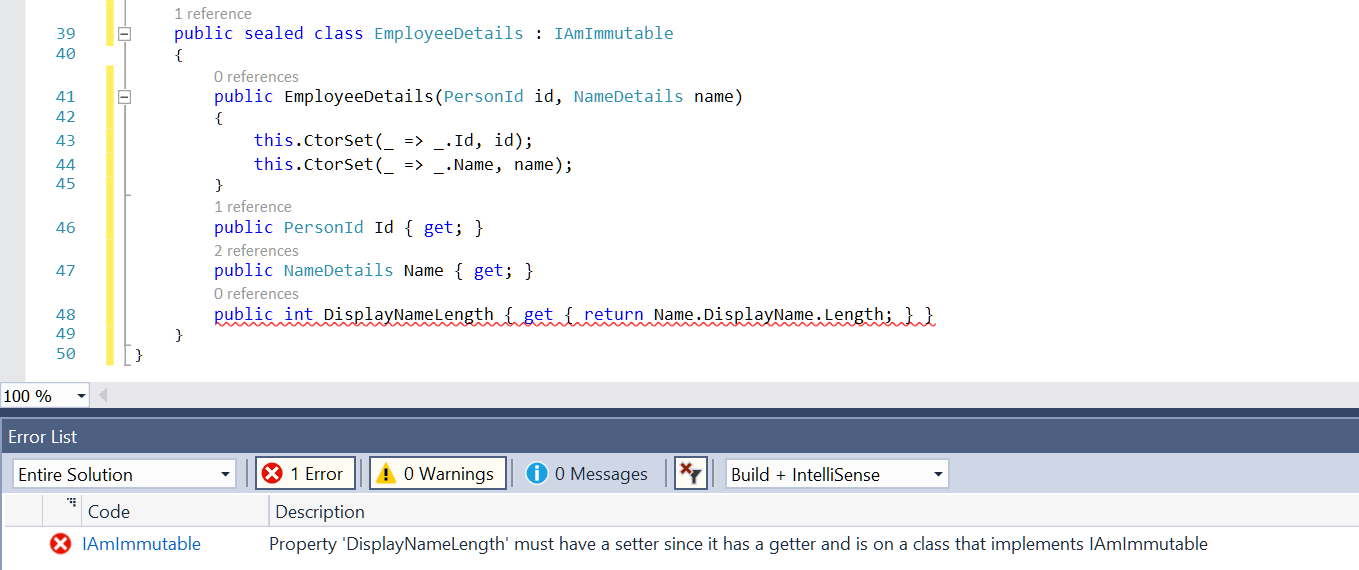

If you forgot this and wrote the following (note the "DisplayNameLength" property that is now effectively a computed value and there would be no way for us to directly set it via a "With" call) -

public sealed class EmployeeDetails : IAmImmutable

{

public EmployeeDetails(PersonId id, NameDetails name)

{

this.CtorSet(_ => _.Id, id);

this.CtorSet(_ => _.Name, name);

}

public PersonId Id { get; }

public NameDetails Name { get; }

public int DisplayNameLength { get { return Name.DisplayName.Length; } }

}

.. then you would see the following errors reported by Visual Studio (presuming you are using 2015 or later) -

.. which is one of the "common IAmImmutable mistakes" analysers identifying the problem for you.

Getting Visual Studio to write code for you, using code fixes

I've been writing more code with this library and I'm still, largely, happy with it. Making the move to assuming never-allow-null (which is baked into the "CtorSet" and "With" calls) means that the classes that I'm writing are a lot shorter and that type signatures are more descriptive. (I wrote about all this in my post at the end of last year "Friction-less immutable objects in Bridge (C# / JavaScript) applications" if you're curious for more details).

However.. I still don't really like typing out as much code for each class as I have to. Each class has to repeat the property names four times - once in the constructor, twice in the "CtorSet" call and a fourth time in the public property. Similarly, the type name has to be repeated twice - once in the constructor and once in the property.

This is better than the obvious alternative, which is to not bother with immutable types. I will gladly take the extra lines of code (and the effort required to write them) to get the additional confidence that a "stronger" type system offers - I wrote about this recently in my "Writing React with Bridge.NET - The Dan Way" posts; I think that it's really worthwhile to bake assumptions into the type system where possible. For example, the Props types of React components are assumed, by the React library, to be immutable - so having them defined as immutable types represents this requirement in the type system. If the Props types are mutable then it would be possible to write code that tries to change that data and then bad things could happen (you're doing something that library expects not to happen). If the Props types are immutable then it's not even possible to write this particular kind of bad-things-might-happen code, which is a positive thing.

But still I get a niggling feeling that things could be better. And now they are! With Roslyn, you can not only identify particular patterns but you can also offer automatic fixes for them. So, if you were to start writing the EmployeeDetails class from scratch and got this far:

public sealed class EmployeeDetails : IAmImmutable

{

public EmployeeDetails(PersonId id, NameDetails name)

{

}

}

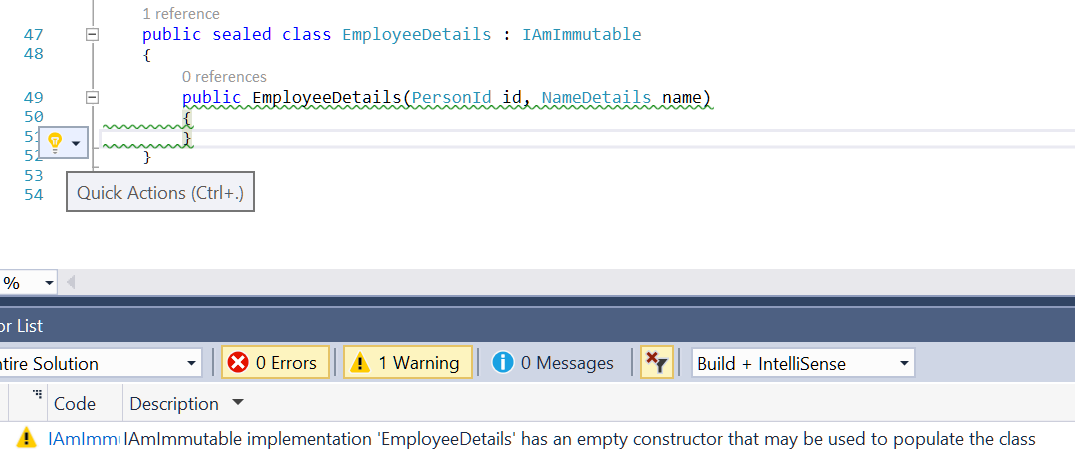

.. then an analyser could identify that you were writing an IAmImmutable implementation and that you have an empty constructor - it could then offer to fix that for you by filling in the rest of the class.

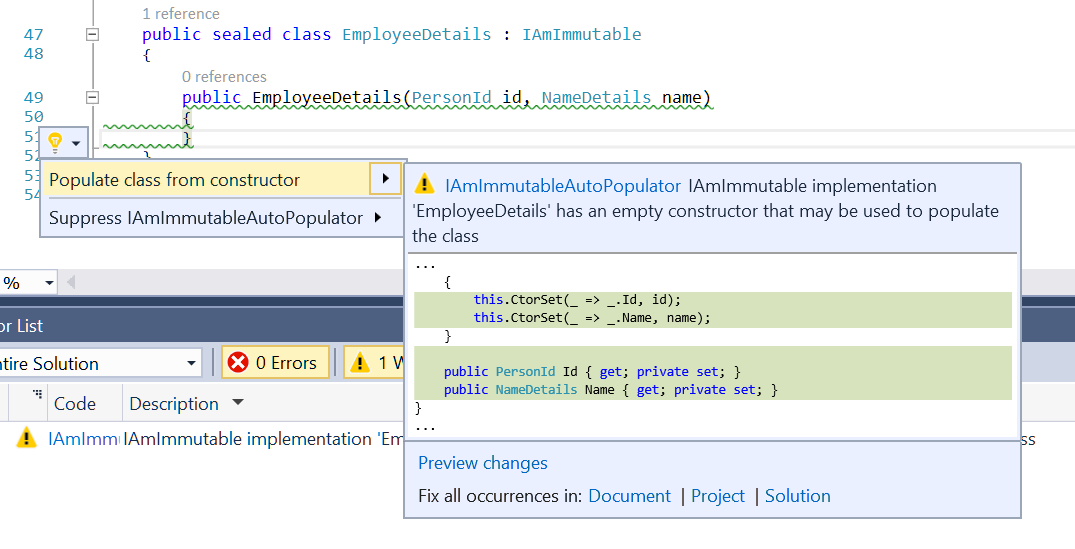

The latest version of the ProductiveRage.Immutable library (1.7.0) does just that. The empty constructor will not only be identified with a warning but a light bulb will also appear alongside the code. Clicking this (or pressing [Ctrl]-[.] while within the empty constructor, for fellow keyboard junkies) will present an option to "Populate class from constructor" -

Selecting the "Populate class from constructor" option -

.. will take the constructor arguments and generate the "CtorSet" calls and the public properties automatically. Now you can have all of the safety of the immutable type with no more typing effort than the mutable version!

// This is what you have to type of the immutable version,

// then the code fix will expand it for you

public sealed class EmployeeDetails : IAmImmutable

{

public EmployeeDetails(PersonId id, NameDetails name)

{

}

}

// This is what you would have typed if you were feeling

// lazy and creating mutable types because you couldn't

// be bothered with the typing overhead of immutability

public sealed class EmployeeDetails

{

public PersonId Id;

public NameDetails name;

}

To summarise

If you're already using the library, then all you need to do to start taking advantage of this code fix is update your NuGet reference* (presuming that you're using VS 2015 - analysers weren't supported in previous versions of Visual Studio).

* (Sometimes you have to restart Visual Studio after updating, you will know that this is the case if you get a warning in the Error List about Visual Studio not being able to load the Productive.Immutable analyser)

If you're writing your own library that has any guidelines or common gotchas that you have to describe in documentation somewhere (that the users of your library may well not read unless they have a problem - at which point they may even abandon the library, if they're only having an investigative play around with it) then I highly recommend that you consider using analysers to surface some of these assumptions and best practices. While I'm aware that I've not offered much concrete advice on how to write these analysers, the reason is that I'm still very much a beginner at it - but that puts me in a good position to be able to say that it really is fairly easy if you read a few articles about it (such as Use Roslyn to Write a Live Code Analyzer for Your API) and then just get stuck in. With some judicious Google'ing, you'll be making progress in no time!

I guess that only time will tell whether library-specific analysers become as prevalent as I imagine. It's very possible that I'm biased because I'm such a believer in static analysis. Let's wait and see*!

* Unless YOU are a library writer that this might apply to - in which case, make it happen rather than just sitting back to see what MIGHT happen! :)

Posted at 22:33

About

Dan is a big geek who likes making stuff with computers! He can be quite outspoken so clearly needs a blog :)

In the last few minutes he seems to have taken to referring to himself in the third person. He's quite enjoying it.

Recent Posts

- Hosting a DigitalOcean App Platform app on a custom subdomain (with CORS)

- (Approximately) correcting perspective with C# (fixing a blurry presentation video - part two)

- Finding the brightest area in an image with C# (fixing a blurry presentation video - part one)

- So.. what is machine learning? (#NoCodeIntro)

- Parallelising (LINQ) work in C#

Highlights

- Face or no face (finding faces in photos using C# and Accord.NET)

- When a disk cache performs better than an in-memory cache (befriending the .NET GC)

- Performance tuning a Bridge.NET / React app

- Creating a C# ("Roslyn") Analyser - For beginners by a beginner

- Translating VBScript into C#

- Entity Framework projections to Immutable Types (IEnumerable vs IQueryable)

Archives

- April 2025 (1)

- March 2022 (2)

- February 2022 (1)

- August 2021 (1)

- April 2021 (2)

- March 2021 (1)

- August 2020 (3)

- July 2019 (2)

- September 2018 (1)

- April 2018 (1)

- March 2018 (1)

- July 2017 (1)

- June 2017 (1)

- February 2017 (1)

- November 2016 (1)

- September 2016 (2)

- August 2016 (1)

- July 2016 (1)

- June 2016 (1)

- May 2016 (3)

- March 2016 (3)

- February 2016 (2)

- December 2015 (1)

- November 2015 (2)

- August 2015 (3)

- July 2015 (1)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- March 2015 (1)

- January 2015 (2)

- December 2014 (1)

- November 2014 (1)

- October 2014 (2)

- September 2014 (2)

- August 2014 (1)

- July 2014 (1)

- June 2014 (1)

- May 2014 (2)

- February 2014 (1)

- January 2014 (1)

- December 2013 (1)

- November 2013 (1)

- October 2013 (1)

- August 2013 (3)

- July 2013 (3)

- June 2013 (1)

- May 2013 (2)

- April 2013 (1)

- March 2013 (8)

- February 2013 (2)

- January 2013 (2)

- December 2012 (3)

- November 2012 (4)

- September 2012 (1)

- August 2012 (1)

- July 2012 (3)

- June 2012 (3)

- May 2012 (2)

- February 2012 (3)

- January 2012 (4)

- December 2011 (7)

- August 2011 (2)

- July 2011 (1)

- May 2011 (1)

- April 2011 (2)

- March 2011 (3)